Foreseeing GE's Fall

A Book Pointed to GE's Red Flags in 1998; and Business Epistemology

tl;dr

A well-researched book from a former WSJ reporter unsurfaced GE’s mismanagement and red flags as early as 1998.

I find it difficult to enjoy narrative business non-fiction due to the narrative fallacy and overdetermination of outcomes, so I now consume such content for entertainment, and to build a library of concept instantiations.

Business Epistemology Is Hard

It’s been hard for me to enjoy narrative business non-fiction since combining the ideas of the narrative fallacy and the overdetermination of outcomes (it’s hard to extract clear lessons from history).

It has also ruined podcasts like Acquired (aka the Narrative Fallacy podcast) or The Knowledge Project (ironic). My quick solution to this is to consume them as entertainment. Then wash them down with tall glasses of cognitive dissonance1.

Books like Lights Out (good) and Power Failure2 (better) have talked about the downfall of General Electric, and the failures of the Jack Welch School of Mismanagement (more like Straight From The Butt, amirite guys).

But I read Thomas Boyle’s At Any Cost: Jack Welch, General Electric, and the Pursuit of Profit as an exercise to figure out how much what led to GE’s subsequent downfall 2007 onward was available to the public when it was published 1998. At the time of publishing, GE was the largest company in the world by market capitalization, and the fifth-largest company in the world by revenue. I read the books in chronological order to have a bit of data hygiene (I had seen the headlines about GE since 2008 but never really dug deep).

Welch and GE thought At Any Cost would be so damaging to their image and made life very hard for the author, Thomas Boyle, and his publisher. They used legal intimidation, and behind the scenes machinations, including a negative review by Businessweek’s John Byrne, who soon after became Welch’s ghostwriter for Jack: Straight from the Gut.

“It became the most adversarial project and frankly, on some level, frightening. I had to go to a place where I could find faith in something larger than myself, and that faith was found in Christ…You feel so threatened and so anxious about a situation that you don’t really have anyplace else to turn, and I turned to God. I prayed every day for four years about that project…You have to lose your life to find it…I truly thank Jack Welch, because he helped to bring me to Christ.”

Boyle now works as the director of communications at a Presbyterian Church in Mount Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

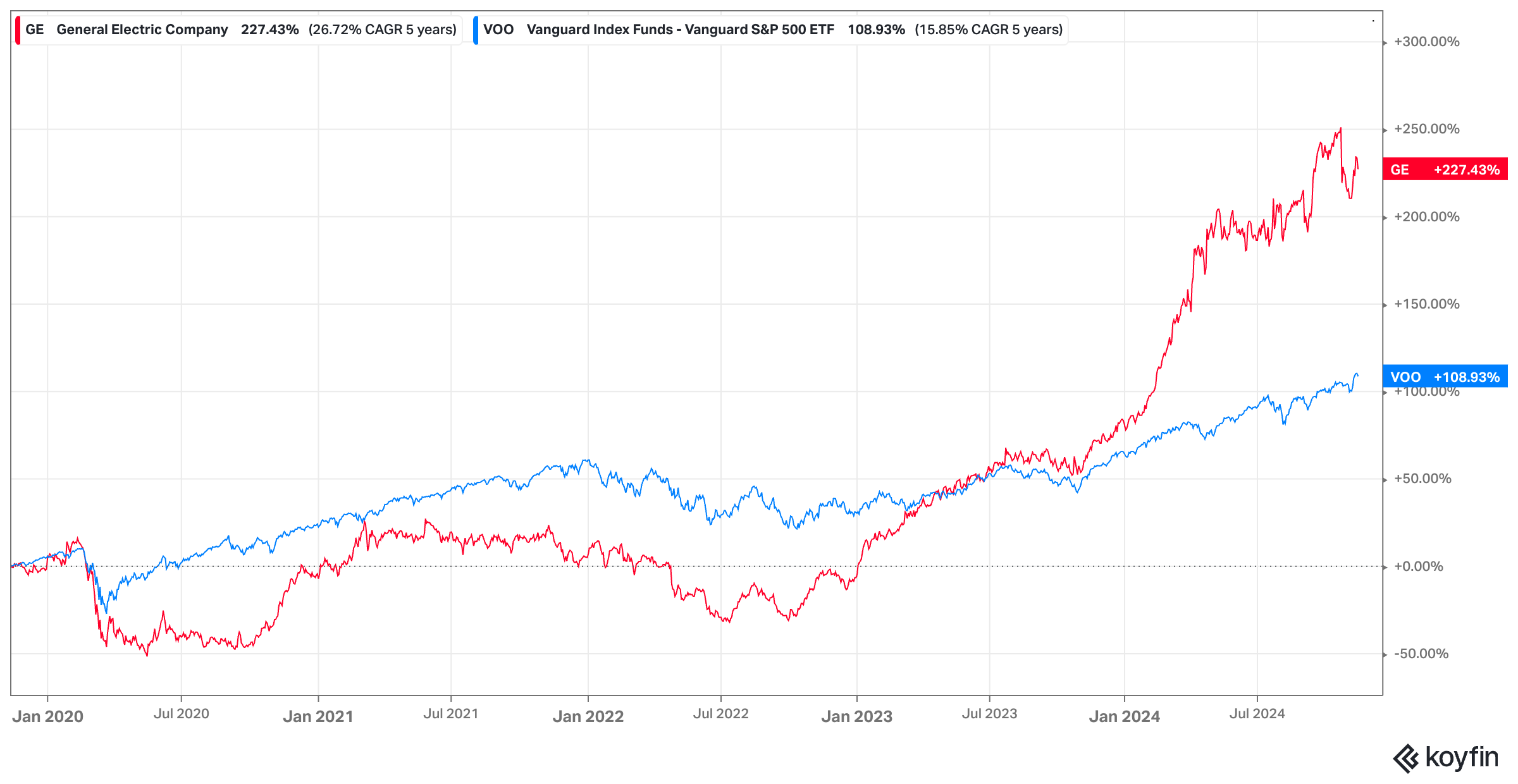

What was the alpha in knowing the issues or pricing them in?

The short answer is none. GE outperformed the S&P500 over the next 1-, 3- and 5 years after the book was published.

The less short answer is ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ because GE’s P/E multiple trended downward after the date of publishing, other prominent analysts and investors like Bill Gross and Jim Grant talked about GE’s complexity–so the overdetermination of failure.

Even so, I’ll summarize some of the issues highlighted by Boyle in At Any Cost, and other anecdotes that I thought were interesting.

Welch's Formative Years and Their Influence on His Leadership

Welch was an only child, obviously. Grace Welch, his mother, instilled ambition, independence, and self-confidence in him which made him a competitive athlete (but not a sportsman) despite his short stature, and helped him overcome his stutter.

An incident involving a denied scholarship for ROTC reinforced Welch’s chip on his shoulder and the feeling of being excluded from elite circles. From the start of his career, Welch displayed a fierce competitiveness, even quitting weekend softball games because colleagues resented his aggressive playing. His colleagues refused to let him join their golf game, further fueling his desire to prove himself.

The “Plastics Culture”

Welch’s early career at GE Plastics shaped his management style. He found Plastics to be a business that matched his aggressive, business as war style. This period also marked the beginning of his Holy Grail of ‘delivering the numbers’, and which over time became the Tyranny of Numbers.

I wonder how much of starting out in a commodity business where the focus is on competing for market share and not thinking of new ways to create and deliver customer value affected Welch’s ideas on business.

Here are other aspects of his time at GE Plastics shaping his worldview:

“Speed, Simplicity, Self-Confidence”: This mantra became central to Welch's leadership philosophy at GE. It emphasized rapid decision-making, streamlining processes, and cultivating a culture of boldness and conviction among managers.

Prioritizing Results Above All Else: Sales targets were relentlessly pursued, and individuals were judged solely on their ability to deliver results. This narrow focus on outcomes carried over into Welch's management style at GE, where he established a system of rigorous performance evaluations and demanded consistent profit growth from every business unit.

Tolerance for Unethical Behavior: Examples include pressuring suppliers to make unreasonable concessions, engaging in questionable accounting practices, and tolerating sexual harassment. While publicly espousing values like integrity and fairness, Welch overlooked these transgressions in the pursuit of financial success. This tolerance for misconduct carried over into Welch's leadership at GE, where he was criticized for prioritizing profits over ethical considerations.

Loyalty as an “antiquated notion”: The focus on performance and constant competition created a climate where job security was tenuous, and individuals were expected to prioritize their own success. Welch actively discouraged loyalty to the company and to individuals, viewing it as an impediment to achieving necessary change.

Creating a Cult of Personality: Welch imprinted his own values and personality onto GE. The “Plastics Culture” became the model for the entire company, with its emphasis on aggression, risk-taking, and results above all else. Welch used training programs, performance evaluations, and constant communication to cultivate a corporate culture that mirrored his own values and priorities.

The Values Hypocrisy: while he publicly championed values like teamwork, empowerment, and integrity, his actions contradicted these principles. The emphasis on individual performance, coupled with his demanding and often intimidating leadership style, created a climate of fear and insecurity within GE.

“A Manager Can Manage Anything” – Welch's View of Management Skill Transferability

Welch believed that management skills were highly transferable across different industries and business types. He did not see specialized knowledge or experience as essential for successful leadership. Welch moved managers frequently between divisions and acquired businesses in diverse sectors, assuming that strong managers could succeed anywhere, similar to how colonial empires transferred their officers from one continent to another.

For instance, Vincenzo Morelli was moved from strategic planning to leading European operations at GE Medical Systems and later considered for a role in European lighting. Similarly, Welch offered to move Bob Bowen, a finance executive, from the troubled Tungsram acquisition to a different role in the US.

Welch sought to instill a uniform management culture across GE, emphasizing his “speed, simplicity, self-confidence” mantra and values like “reality-based thinking”. He used training programs to indoctrinate managers into this culture, aiming to create a cohesive leadership force that could be deployed throughout the company.

He aggressively acquired companies in various fields, including financial services (Kidder, Peabody) and entertainment (NBC, and RCA), even though GE had little prior experience in these sectors. He believed that by installing strong GE managers with proven track records, these businesses could be successfully integrated and driven to profitability.

In some cases, moving strong managers into new areas led to improvements in efficiency and profitability. The turnaround at NBC is cited as an example where Welch's approach yielded positive results. In other instances, the lack of industry-specific knowledge among transferred managers contributed to problems. The disastrous acquisition of Kidder, Peabody is a prime example.

The BCG Pipeline

Related to management skill transferability, Welch viewed BCG as his “farm team”, he identified promising talent and elevating them to leadership roles within the company. Welch actively recruited consultants from BCG, often placing them in strategic planning roles at GE headquarters. This initial assignment allowed them to familiarize themselves with the company's operations and demonstrate their capabilities.

Consultants who performed well in their initial roles were rapidly promoted to leadership positions within various GE divisions, often managing teams of employees significantly older and more experienced than themselves. This practice highlights Welch's confidence in the skills and perspectives of BCG alumni, even if it potentially created resentment among long-time GE employees who perceived these promotions as favoritism.

[Vincenzo] Morelli, on the other hand, represented everything that Welch found appealing. An Italian national, he was cosmopolitan, young, smart, and spoke English with a thick British accent that Welch found captivating. Morelli not only had looks and breeding; he had the proper CV, having worked previously at the Boston Consulting Group, a farm team for General Electric from which Welch plucked the most promising talent and elevated them to the big time. The drill was always the same: Once hired in, the new recruit would do a short boot camp in some corporate function at headquarters, in Morelli’s case on the planning sta Carpenter, another BCG alum, headed. If the recruit performed satisfactorily, he would be given a plum job running a GE operation somewhere in the empire, commanding people twice his age, and putting the techniques Welch had taught into practice.

While the positive of having BCG consultants in had the expected benefits of a shared business philosophy (analytical, results-orientated approach ) and fresh perspectives, the downsides were the cultural cash, lack of institutional knowledge, and lack of development of internal talent. Welch's focus on financial performance and his reliance on Strategy Guys shifted GE's attention away from its traditional strengths in technological innovation, potentially contributing to the company's eventual decline in certain industries, reflecting a broader trend in the American economy towards favoring financial engineering, at the expense of deep industry expertise and value-creation.

Earnings Management at GE

The pressure to meet earnings targets, stemming from Welch's leadership, created an environment where managers felt compelled to engage in earnings management.

This is a partial list of earnings management/earnings smoothing maneuvers:

Selling the Asahi Diamond Reserve: GE Plastics, facing pressure to meet earnings targets in 1989, sold its 10% stake in Japan's Asahi Diamond Industrial Company to Mitsui with an unwritten buyback agreement. This allowed GE to book a $67 million gain, and boost reported earnings despite objections from the corporate accounting department who warned of potential legal issues related to “stock parking.”

The Midnight Flight: GE's Electrical Distribution & Control business loaded a cargo plane with inventory before a year-end count and flying it to Puerto Rico. This maneuver aimed to lower the inventory valuation and inflate earnings, taking advantage of accounting rules that allowed for inventory to be excluded from the count if it was in transit.

Exploiting Accounting Flexibility: GE leveraged the discretion allowed under GAAP principles to assign favorable values to assets and influence reported earnings. For instance, when GE acquired RCA, they allocated a significant portion of the goodwill to NBC. This increased the network's book value and allowed GE to book higher profits when other RCA assets were sold.

Sale and Leaseback Transactions: GE Plastics used sale and leaseback transactions to generate “earnings”. This involved selling fixed assets like machinery or even entire plants to a third party and then leasing the assets back. This generated an immediate capital gain that GE could book as income, even though the underlying economics of the business remained unchanged and the deal was done at disadvantageous terms.

Systematic Harassment Of And Retaliation Against Whistleblowers

The company's focus on profits and performance, coupled with a culture of fear and intimidation, may have created an environment where dissent was not tolerated and where those who spoke out about wrongdoing faced intense retaliation.

Vera English worked as a technician at a GE nuclear fuel facility in Wilmington, North Carolina. In the late 1970s, she began reporting health and safety violations, which she eventually brought to the attention of the federal government. As a result of her whistleblowing, English experienced a campaign of harassment and intimidation. Her home was burglarized and vandalized on multiple occasions, she received obscene phone calls, gunshots were fired at her home. English was also ostracized by many in her community, including fellow GE employees who saw her as a troublemaker. A letter published in the local newspaper accused her of harming the community and stated that she deserved no thanks for her actions. English ultimately lost her job and faced significant financial hardship. She also experienced severe emotional and psychological distress, and required therapy for many years.

Jack Shannon worked as a nuclear engineer at the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory, a facility operated by GE for the Navy. He began raising concerns about safety violations in the early 1980s, which led to his demotion and ultimately his departure from the company. He faced retaliation for his whistleblowing, including negative performance reviews, threats of salary reduction, and pressure to see a psychologist. His managers also placed false and derogatory information in his personnel security file. Shannon's efforts to expose safety issues at Knolls were met with resistance and attempts to silence him. He was told that his concerns were unfounded and that raising them only contributed to unnecessary fear and increased operating costs.

Frank Bordell, a health physicist at Knolls, reported safety violations related to potential radiation exposure of employees. His concerns were ignored by management, leading him to file a complaint with the Department of Energy Inspector General. GE fired Bordell after he filed his complaint and then engaged in lengthy legal battles to prevent him from getting his case heard in court.

Doug Allen was a union leader at Knolls who also experienced harassment for his activism and whistleblowing. He had compiled a “death list” of over 150 employees who had died, many from cancer. While not all of these deaths can be definitively linked to workplace hazards, the high rate of cancer among Knolls workers, especially those exposed to asbestos and radiation is anomalous. Allen fought for nearly a decade to expose the asbestos problem at the facility and was featured in the Oscar-winning documentary Deadly Deception, which highlighted GE's involvement in nuclear weapons and safety violations. In retaliation for his actions, GE management targeted Allen and the union. Union jobs were eliminated, and union members had their security clearances challenged and revoked, preventing them from working at Knolls.

A partial list of other ethical/criminal lapses at GE from the book

Kidder, Peabody Scandal: Welch's close associate, Mike Carpenter, was put in charge at Kidder despite having no Wall Street experience. Welch's inattention to red flags allowed bond trader Joseph Jett to exploit the system for personal gain and create $350 million in fake profits.

Minuteman Missile Contract: GE was indicted in 1985 for fraud on a Minuteman missile contract and was suspended from doing business with the government. Welch met with Air Force Secretary Verne Orr and made statements that led Orr to lift most of the suspension. However, the U.S. attorney later argued that Welch deceived Orr to get the sanctions lifted. After the government obtained documents that GE had withheld, GE was found guilty, two managers were jailed, and the company paid $36 million in fines and restitution.

The Dotan Affair: GE executives, including Welch, were aware of the illegal activities of an Israeli general, Rami Dotan, and a GE executive, Herbert Steindler, involving fraudulent use of U.S. military aid to Israel. This led to a $42 million fraud and the arrest of Dotan. Welch tried to shift blame onto lower-level employees, but Congressional investigations revealed that Welch himself had knowledge of the fraud. Welch was compelled to testify before a Congressional subcommittee, marking the first time he publicly admitted that his company had broken the law.

Antitrust Violations related to Superabrasives and De Beers: Ed Russell, a former vice president at GE's Superabrasives unit, alleged that Welch had knowledge of antitrust violations related to price-fixing with the De Beers diamond cartel. Though Welch denied these claims, the case was ultimately settled out of court, leading to speculation about the validity of the allegations. This incident highlighted the pressure to achieve market dominance at any cost under Welch's leadership.

PCBs in the Hudson River: Welch downplayed the dangers of PCBs (highly toxic chemical & a carcinogen) in the Hudson River and resisted environmental remediation efforts, prioritizing cost savings over environmental responsibility. He leveraged GE's philanthropic donations to influence New York's environmental policies.

Hanford Nuclear Site: GE faced scrutiny and negative publicity for its mismanagement that led to environmental damage and health risks at the Hanford Nuclear site, a government facility where GE had managed plutonium production for nuclear weapons.

Sexual Harassment: the book described a disturbing practice at GE Plastics known as the “force f*ck” where male superiors would slip their room keys into the pockets of female subordinates during social events. Rebecca Deitz, a former employee, recounted how Uwe Wascher, a high-ranking executive, playfully hitting women on the backside with a bullwhip at a company event and she detailed other examples of the degrading comments she experienced, such as “I can see your nipples with that bra on” and “Your ass is getting a little big, Becky. You better hit the gym”. Despite complaints and documented misconduct, nothing was done to address the sexual harassment at GE Plastics. Deitz notes that many men felt their behavior was acceptable because of rumors about Welch's past conduct within the division. The inaction contributed to a culture of impunity and allowed the harassment to continue unchecked.

As of pixel time, GE’s stock price is headed in the Northeasterly direction while it goes through a turnaround and transformation so I will read Reenergized: The Rise, Fall, and Rise of GE, should someone write it.

GE vs S&P 500, 5-year performance

A better alternative: hold the lessons from history loosely and don't read history for lessons - read to build a library of concept instantiations, not generalizable lessons. Also see The Cynic’s Guide to Reading Business Books.